The history of drag as its own form of performance art (as well as male/female impersonation and mimicry, as these practices were known) stretches much further back in U.S. history than many people may realize. The first known drag ball in the U.S. took place in New York City at Harlem’s Hamilton Lodge in 1869.

For a stretch of time at the turn of the century, gender-bending entertainment was quite popular in the United States. This coincided with the commerciality of vaudeville. However, in the 1940s and 50s (and beyond), “male/female impersonation” offstage was a heavily criminalized behavior. In various places throughout the country, people could be fined or arrested for dressing in attire intended of the opposite sex. Law often dictated a specific number of garments that would determine an outfit to be in violation. This cultural attitude of social conservatism and homophobic paranoia is challenging to square with the knowledge that gender impersonation had been widely regarded as a legitimate (and popular) form of entertainment in decades prior.

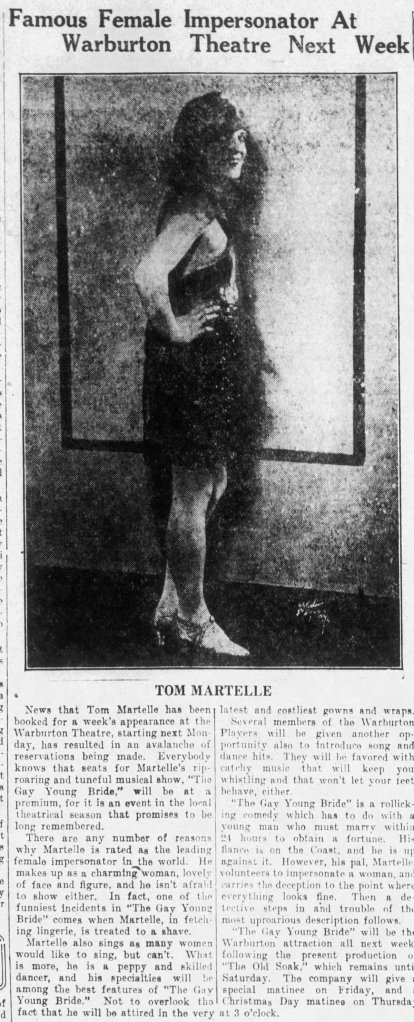

Wed, Dec 17, 1924, Page 5

Given its proximity to New York City, it is unsurprising that drag/impersonation performance made its way to Westchester prior to most other places in the country on a number of recorded occasions. The first of these advertised performances discovered by the Westchester LGBTQ+ History Project occurred in 1897. In this performance, “male impersonator” Lou Rochefort appeared at the Mount Vernon Music Hall.

White Plains, New York

Thu, Aug 5, 1897

Page 1

Other Male impersonators who are known to have performed in Westchester in the 20th century include Kitty Doner and Vera Post.

Kitty Doner, who lived from 1896-1988, was a highly successful vaudeville entertainer and Westchester resident.

According to “Glitter and Concrete: A Cultural History of Drag in New York City” by Elyssa Maxx Goodman, she was known as “the Best Dressed Man on the American Stage.”

As per various newspaper articles published in the 1920s and 1930s, Kitty lived in Larchmont, where she eventually also directed a studio for training young people in singing, dancing, radio technique, instrumentation, and drama. It is likely that she inherited the Larchmont property from her mother, as was reported in a 1923 newspaper article. Even after the height of vaudeville had passed, Kitty gave local performances in Westchester as late as 1938.

According to feminist and queer performance studies scholar Emma Squire, who wrote a masters thesis that heavily centered around Kitty’s life and work, Kitty’s persona in the press was highly centered around her implied femininity (despite her performance style). This included references to her rustic lifestyle “upstate,” tending to her farm.

In reviews, Kitty’s performance was described as “boyish” (rather than manly) and her appearance was described as “pretty.” According to these various reviews, her appearance and mannerisms were such that she would not easily be actually mistaken for a man onstage. Squire notes that this may have been informed by cultural attitudes of the time. It may also have been a contributing factor in her popularity and commercial success.

“The spectator was reassured in her white and heterosexual femininity because heteronormative cultural attitudes created a lens from which the audience viewed Doner,” writes Squire. “I argue that while the press codes Doner’s reproduction of ethnic and class-based white masculinities as a failure because of societal and self-codification of Kitty’s white femininity, Doner created a performer persona which neither adhered to dominant/normative notions of masculinity nor femininity. Rather, as I argue throughout this chapter, she crafted a gender fluid and queer persona under the safe guise of ‘male impersonator.’”

Though typically characterized in interviews and articles by journalists of the time as being feminine, Kitty was quoted in one women’s magazine in 1915 as saying, “If the police weren’t so sharp-sighted, I’d abandon skirts altogether, even for the street, and wear boys’ duds.”

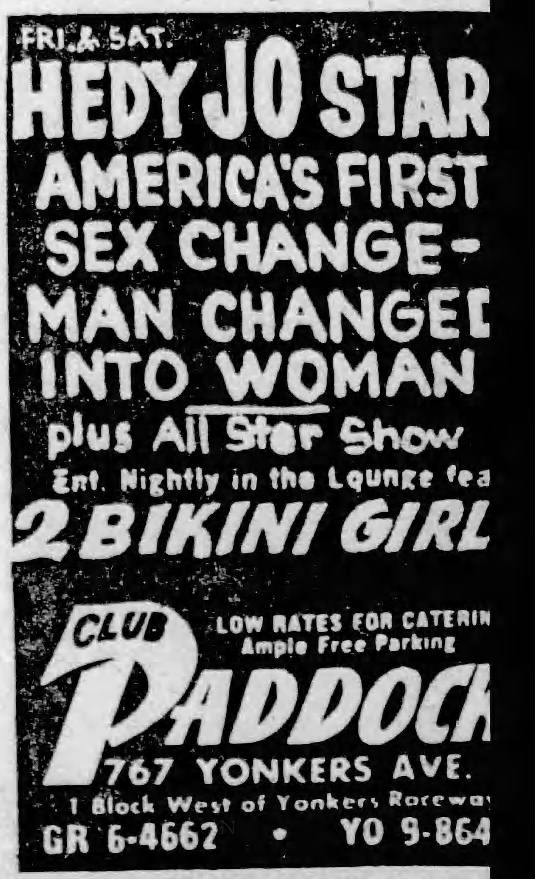

Another famous performer to grace a Westchester stage in the 20th century was Hedy Jo Star.

Star, who penned a memoir entitled “I Changed My Sex!” in 1954, was well-known across the country. She was a carnival worker and later a professional costumer.

White Plains, New York, Fri, Aug 27, 1965

Page 2

Throughout the years, theatrical performances centered around “impersonation” and gender-bending continued at various bars, lounges, and businesses within the county.

Yonkers, New York, Fri, May 21, 1971

Page 14

Editors Note: The gender identity or sexual orientation of any performer mentioned in this post is not something one can expect to ascertain simply based on the historical record. The Westchester LGBTQ+ History Project makes no attempt to infer how these performers identified at the time or how they might identify if they were alive today. However, various gender and sexuality scholars have posited the notion that drag/impersonation/illusion performance in the 19th and early 20th century can be viewed as inherently queer as a phenomena that intentionally subverted heteronormative/gendered cultural roles.

Leave a comment